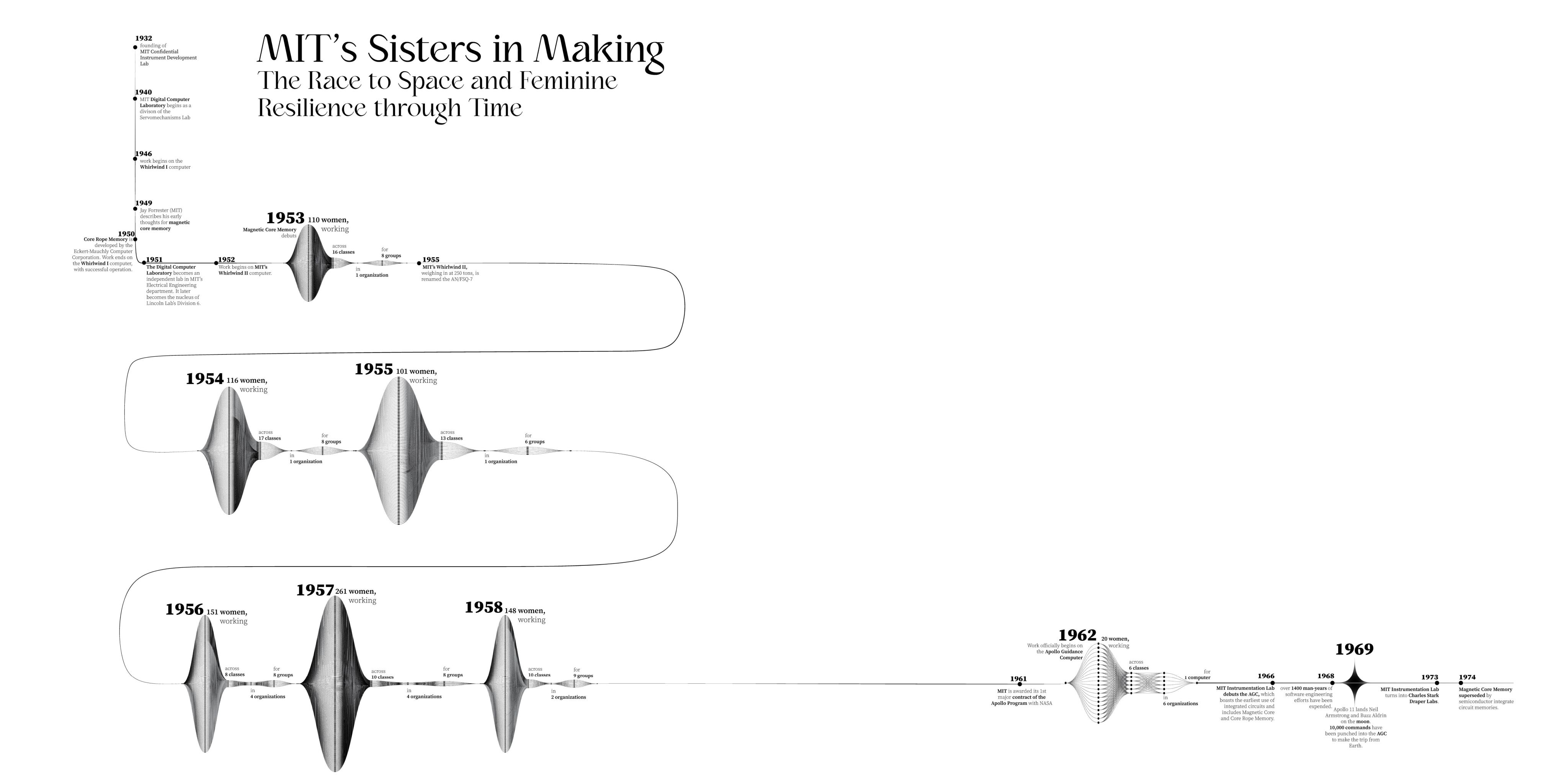

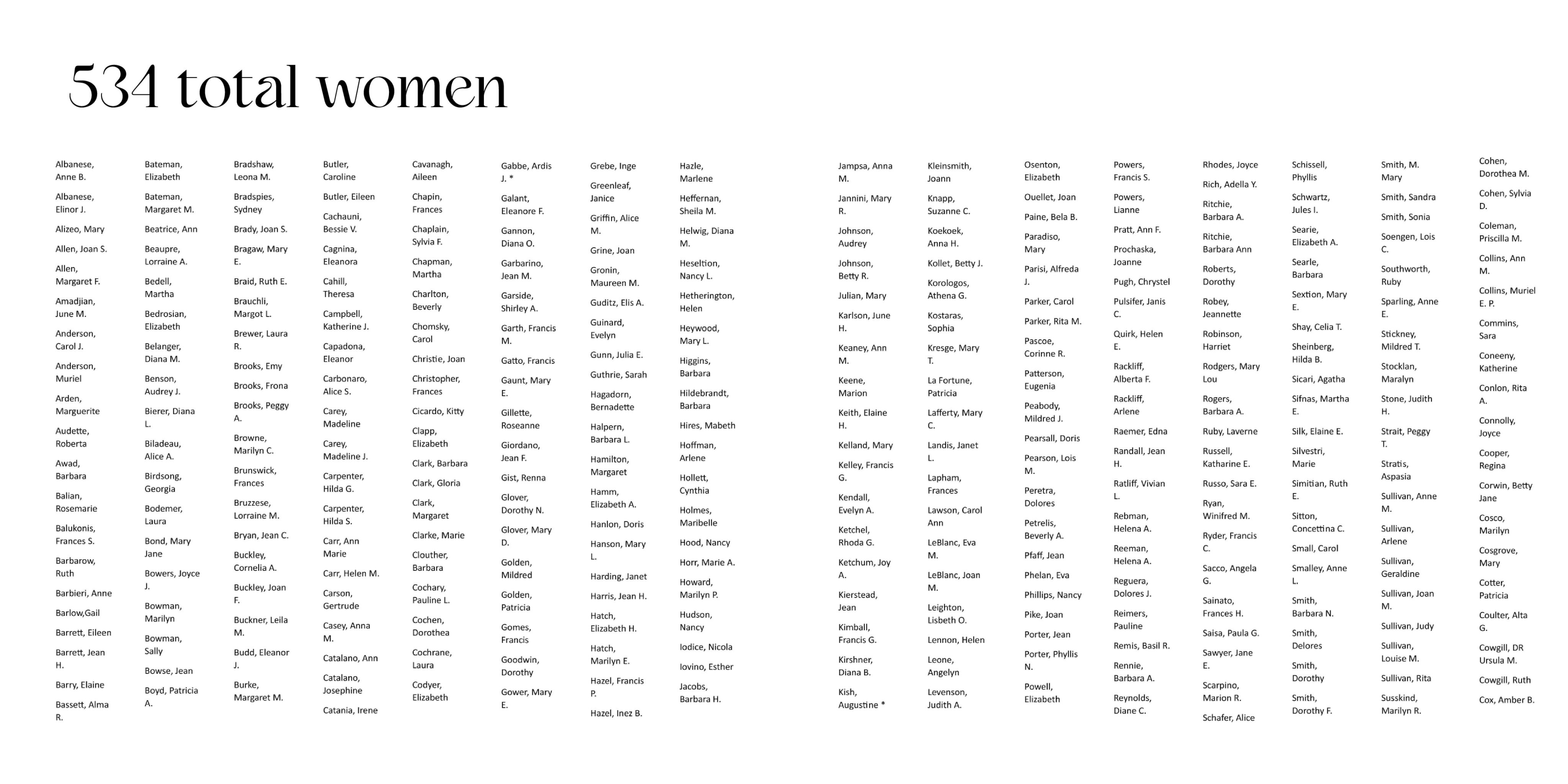

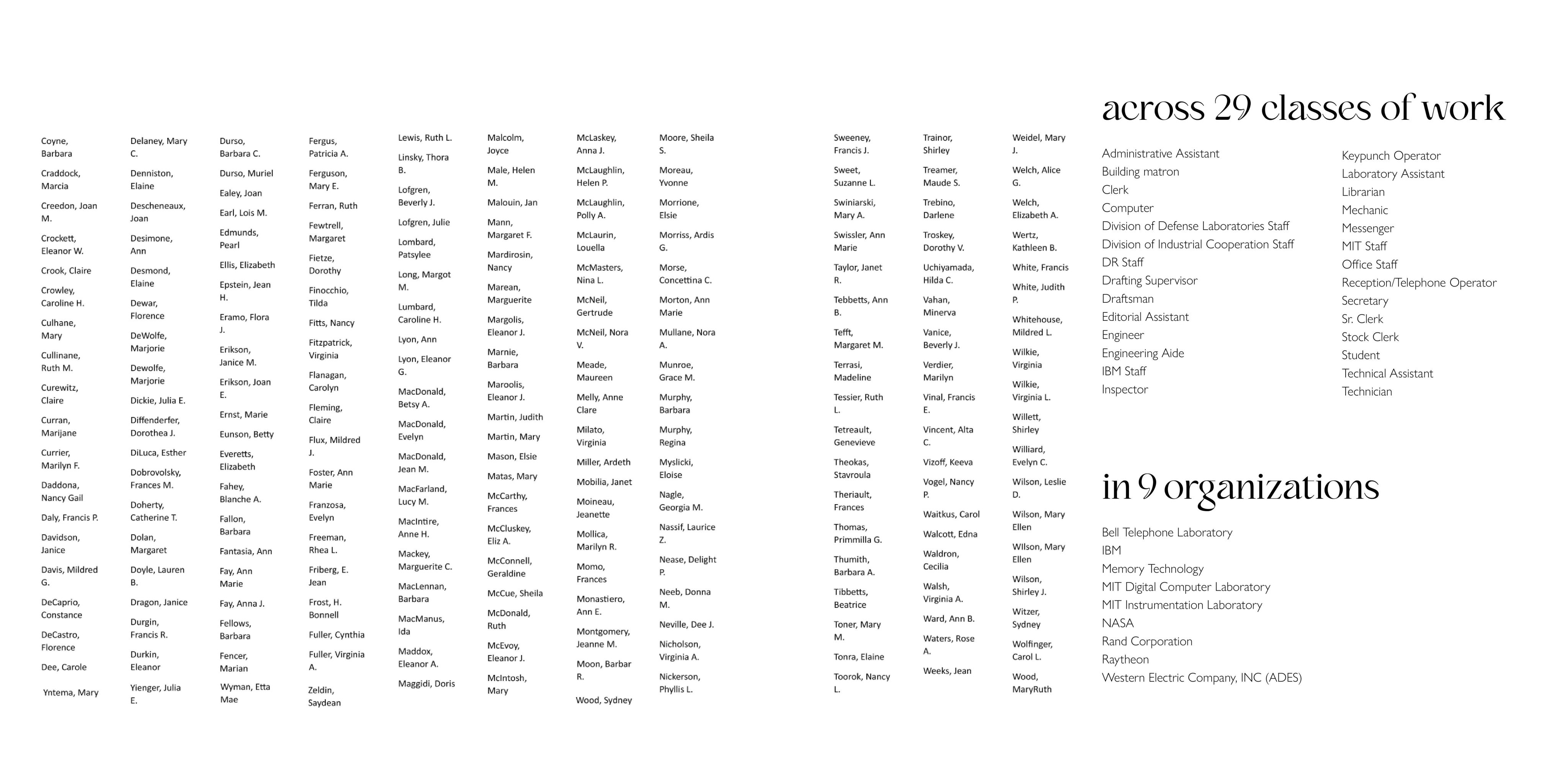

Sisters in Making

Tucked in the documentation of the Apollo 11 mission but rarely mentioned, are the women of different skill sets, across partnering organizations and in different fields of work that contributed to the success of the mission.

The Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) was central to that success as it was a compact integrated processing system unlike anything that had come before. The development of the technology was carried out at the MIT Instrumentation Lab in the 60s, in collaboration with sub contractors such as Raytheon who were tasked with producing the final hardware to be flown to space. Crucial to the AGC and the cascading development of computers was its memory, a woven form of data storage that fulfilled the requirements for lightness, compactness, indestructibility necessary for the Apollo 11 spacecraft.

The focus of this project then are the women who had a hand in the prototyping, testing and fabrication of the woven core memory and core rope memory modules that took humanity to the moon.

Sisters in making as we are calling them are the Space Age weavers, Technical Assistants, Rope Mothers, Technical Assistant, Little Old Ladies, Keypunch Operators and a range of other names and roles as they were known, that contributed to the fabrication of woven memory.

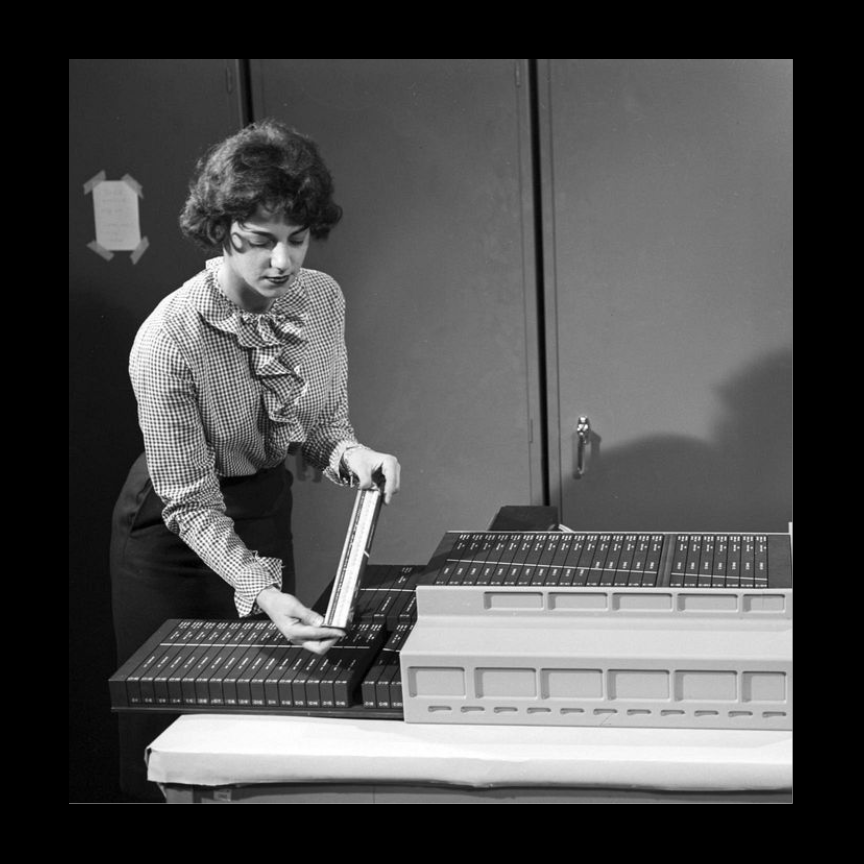

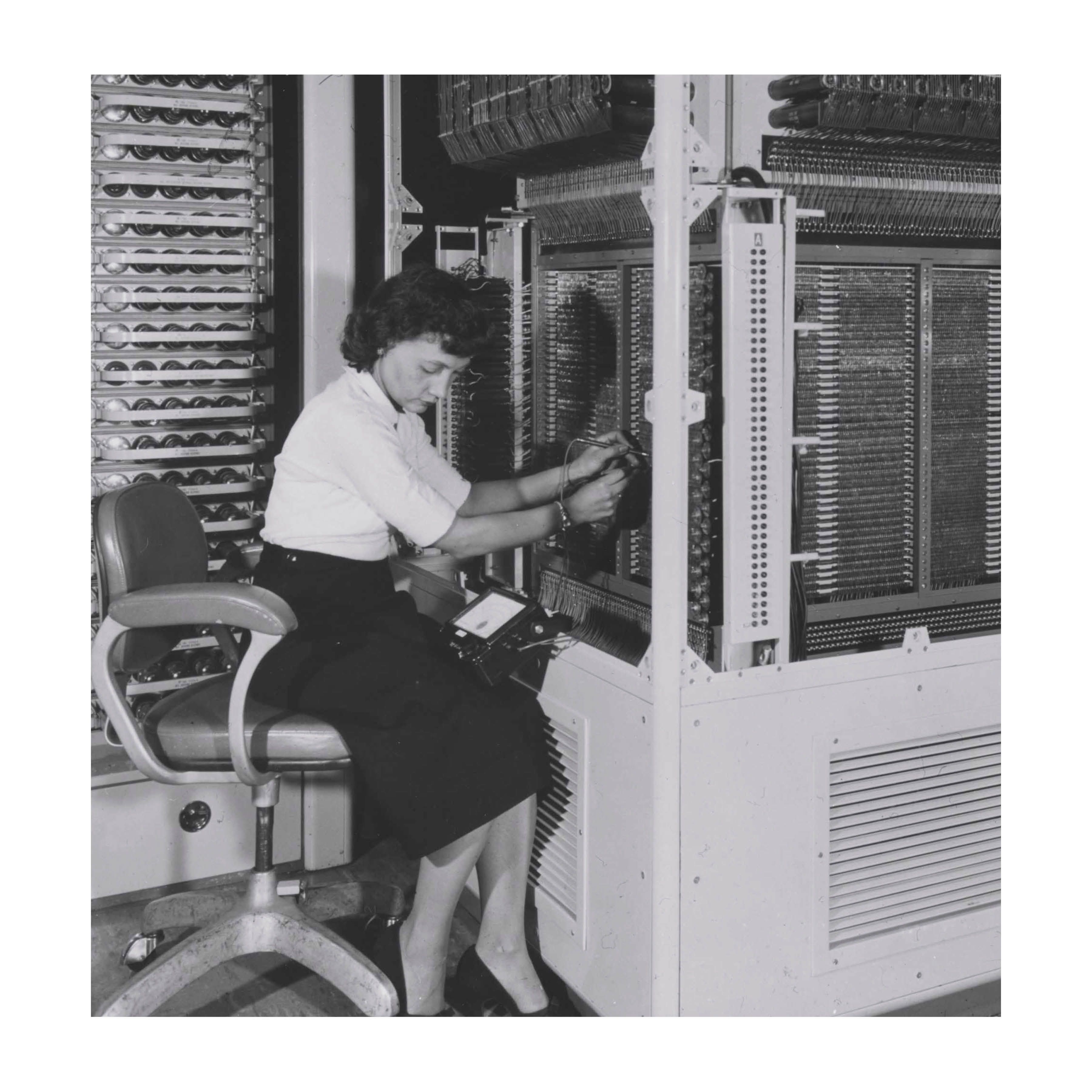

Left:

E (IM) - 15(2). 1960s

A technician assembling the micrologic and core memory panels that make up the Apollo Guidance Computer into their housing.

Rope Mothers

The Core Rope Memory of the AGC, was software woven as hardware. Once woven, it could not be changed and so it was imperative that the code was fine tuned and tested rigorously months in advance. The nature of Core Rope memory put significant pressure on the MIT and NASA programmers to get it right.

The Instrumentation lab assigned people called 'rope mothers’ the responsibility of parenting the development of the software. They were to make sure that the software was programmed correctly. The software was designed so the AGC could perform multiple tasks at once, transmitting data to NASA, calculating trajectory etc.

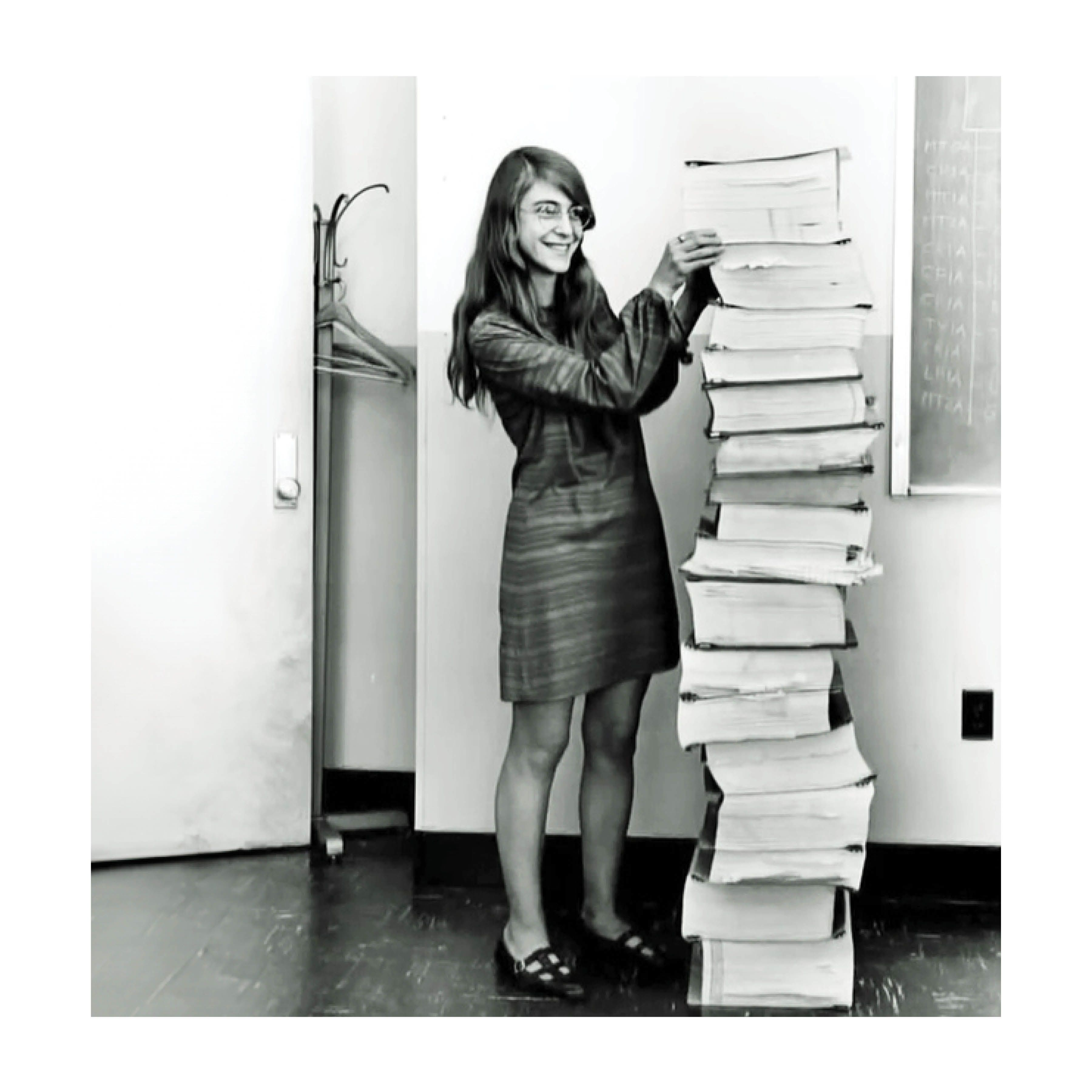

Margaret Hamilton, was one of those Rope Mothers. In this image, she stands beside code listings of the Apollo Guidance Computer that contained results of Guidance equation calculations. She was the head of a team at the Instrumentation lab dedicated to writing and testing Software for the two Apollo 11 computers, one for the command module and one for the Lunar Ejection Module.

Left:

E (IM) - 29 (1), 192-1970

Margaret Hamilton standing next to listings of the Apollo Guidance Computer Source Code

Keypunch Operator

After the code listings were checked by the Rope Mothers, a keypunch operator would create holes in paper cards, keying in the codes into what were known as punhchcards. This method of coding can be traced to weaving techniques, especially the jacquard loom.

Elaine Denniston is a sister in making who was a keypunch operator at the MIT Instrumentation Lab during the Apollo mission. She was responsible for typing up programs onto IBM cards and would proofread the code in the process.

In 2019, Dan Lickly who was also a rope mother and Elaine’s boss at the time, recalled her work at the MIT Instrumentation Lab “And of course these prima donna programmers would be late, ‘I got to do this over,’ ‘Give me another half hour,’ and so on and so on. [Denniston] had to go around at night before she left and beat up on all these programmers to get their information, run it, make sure there were no errors in it, and then turn it in for the overnight run.”

Left:

E (IM) - 11 (1), 1960s

Aperture Punch Card from the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory

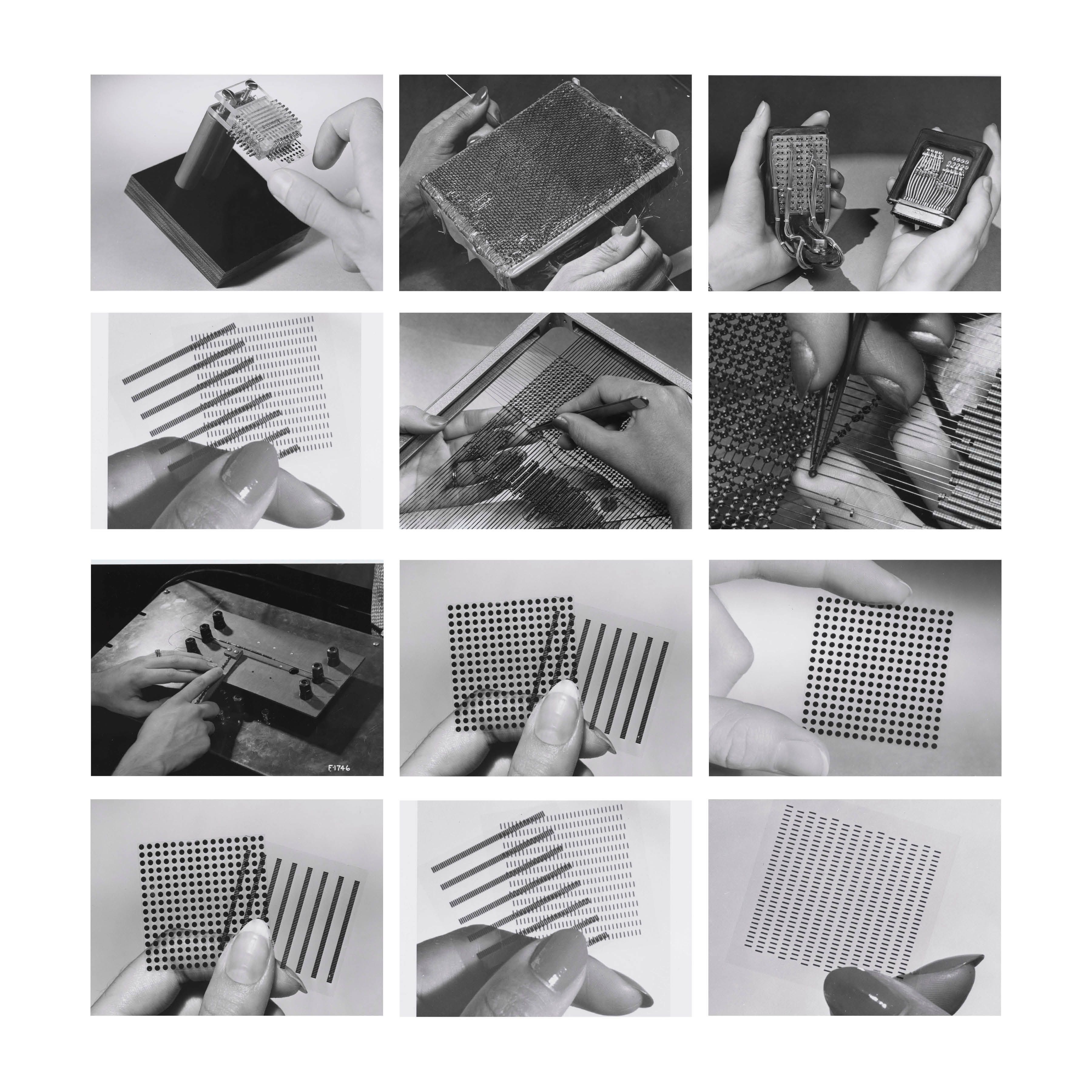

Prototyping

In the documentation of the development of Core Rope Memory at the Instrumentation lab, one comes across pictures like these, that are evidently female hands holding onto prototypes of memory.

Little exists by way of the day to day activities of the teams involved, but there is a statement to be made about the delicate, tedious and repetitive nature of woven memory fabrication, falling to those who were seen as having the dexterity and patience to carry out the required task.

Once each memory prototype was made, it was passed through rigorous testing to detect aspects of failure. Depending on results, it will be remade and retested again.

Opposite:

(Clockwise from left)

A (IM) - 2(3), 1954-1962, 45276

72 Thin Film Memory Plane with Hands

A (IM) - 2(4), 1954-1962, 45276

37 Ferrite Memory Plane with Hands

A (IM) - 2(5), 1954-1962, 45276

Hands holding Prototype for MTC

A (IM) - 2(6), 1954-1962, 45276

Hands stringing 128 x 128 Magnetic Memory Plane

A (IM) - 2(7), 1954-1962, 45276

Hands stringing 64 x 64 Digit Plane Fabrication

A (IM) - 2(8), 1954-1962, 45276

Hands holding 52 Magnetic Array Memory

A (IM) - 2(9), 1954-1962, 45276

Hands mounting ferrite cores for Pulse Test A (IM) - 2(10), 1954-1962, 45276

Hand holding 210 Memory Spots

A (IM) - 2(11), 1954-1962, 45276

Hand holding 115 Thin Film

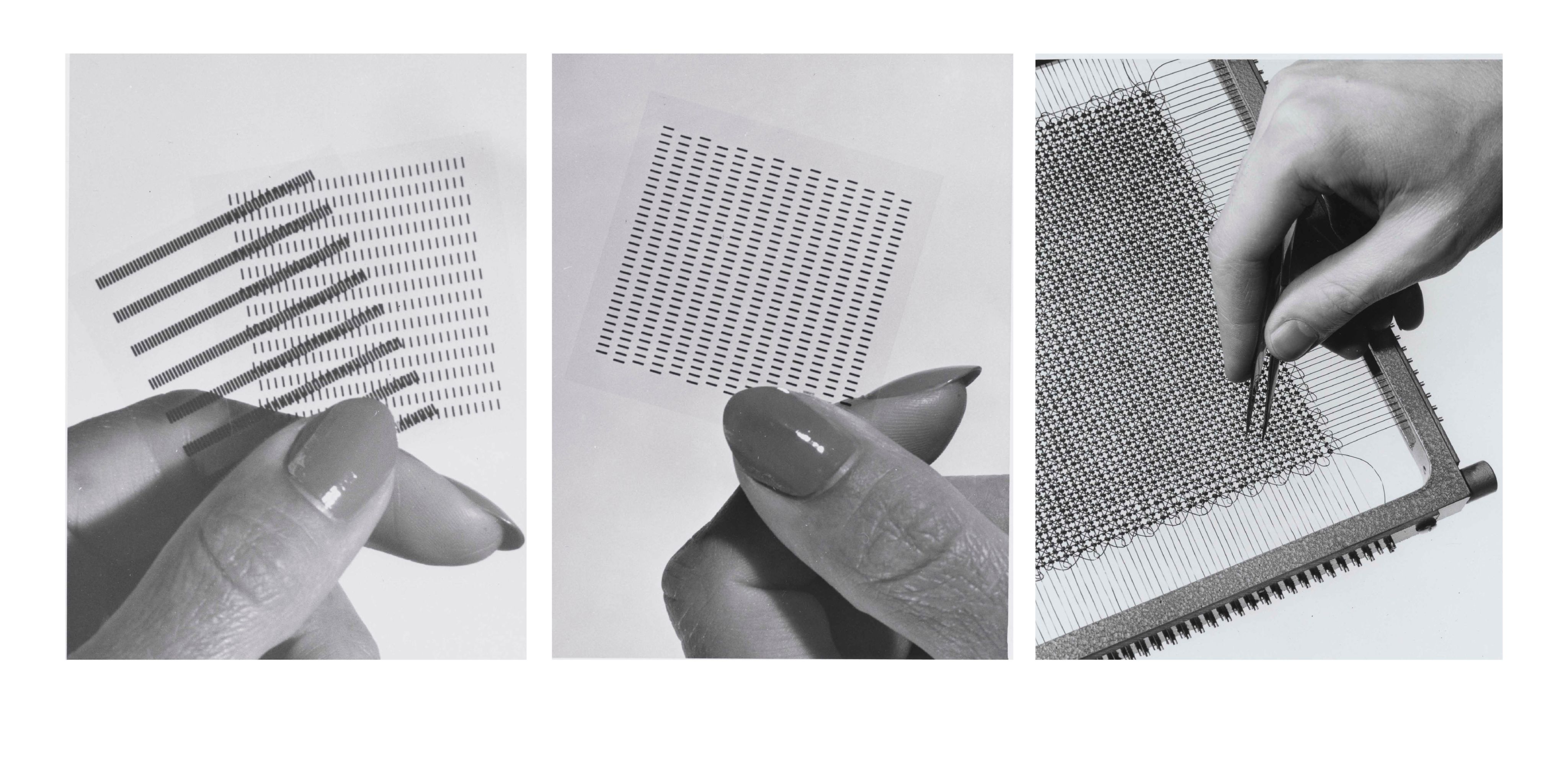

Top:

A (IM) - 2(12), 1954-1962, 45276

Hand holding 52 Magnetic Film Array Memory

A(IM) - 2(13), 1954-1962, 45276

Hand holding 51 Magnetic Film array Memory

A (IM) - 2(6), 1954-1962, 45276

Hands stringing 128 x 128 Magnetic Memory Plane

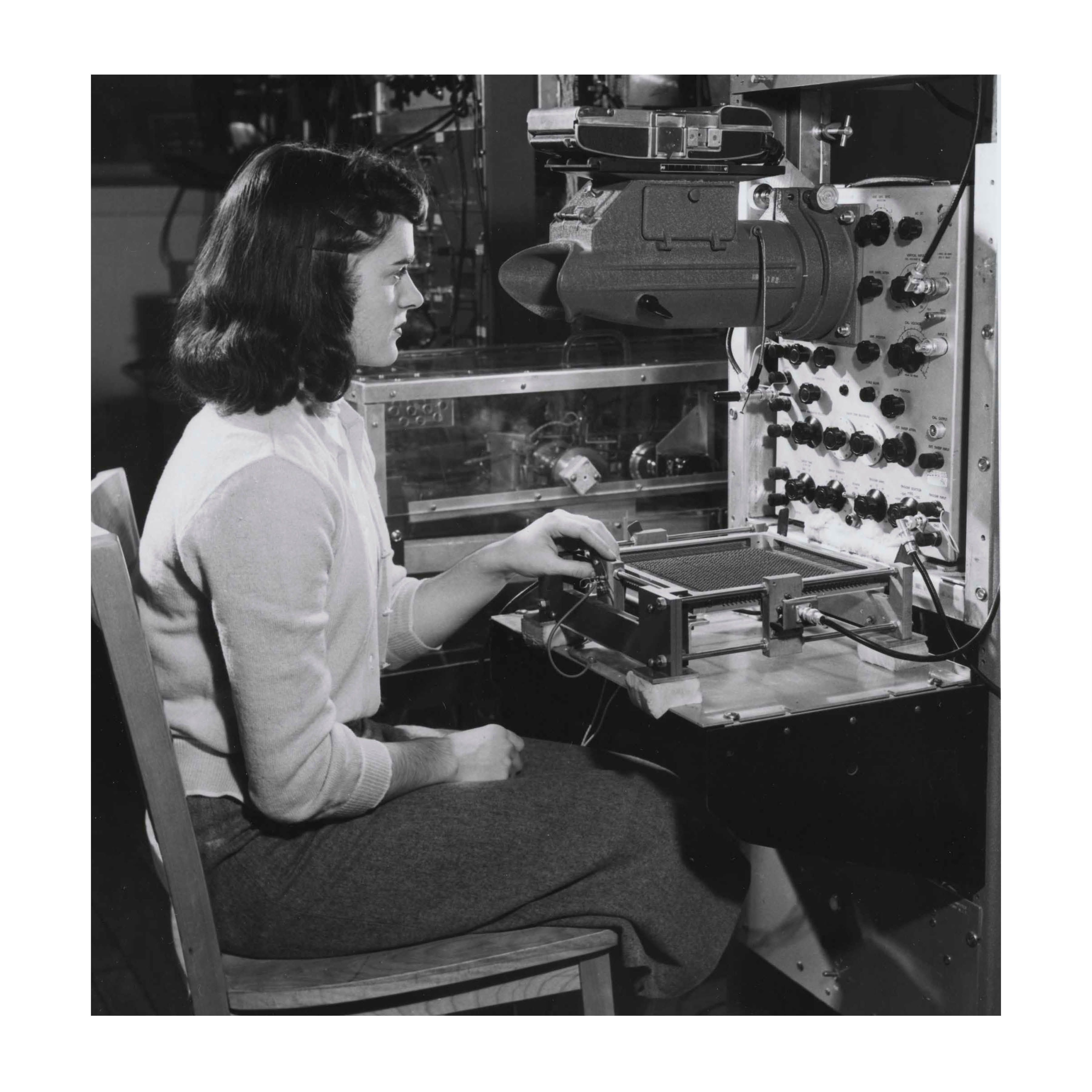

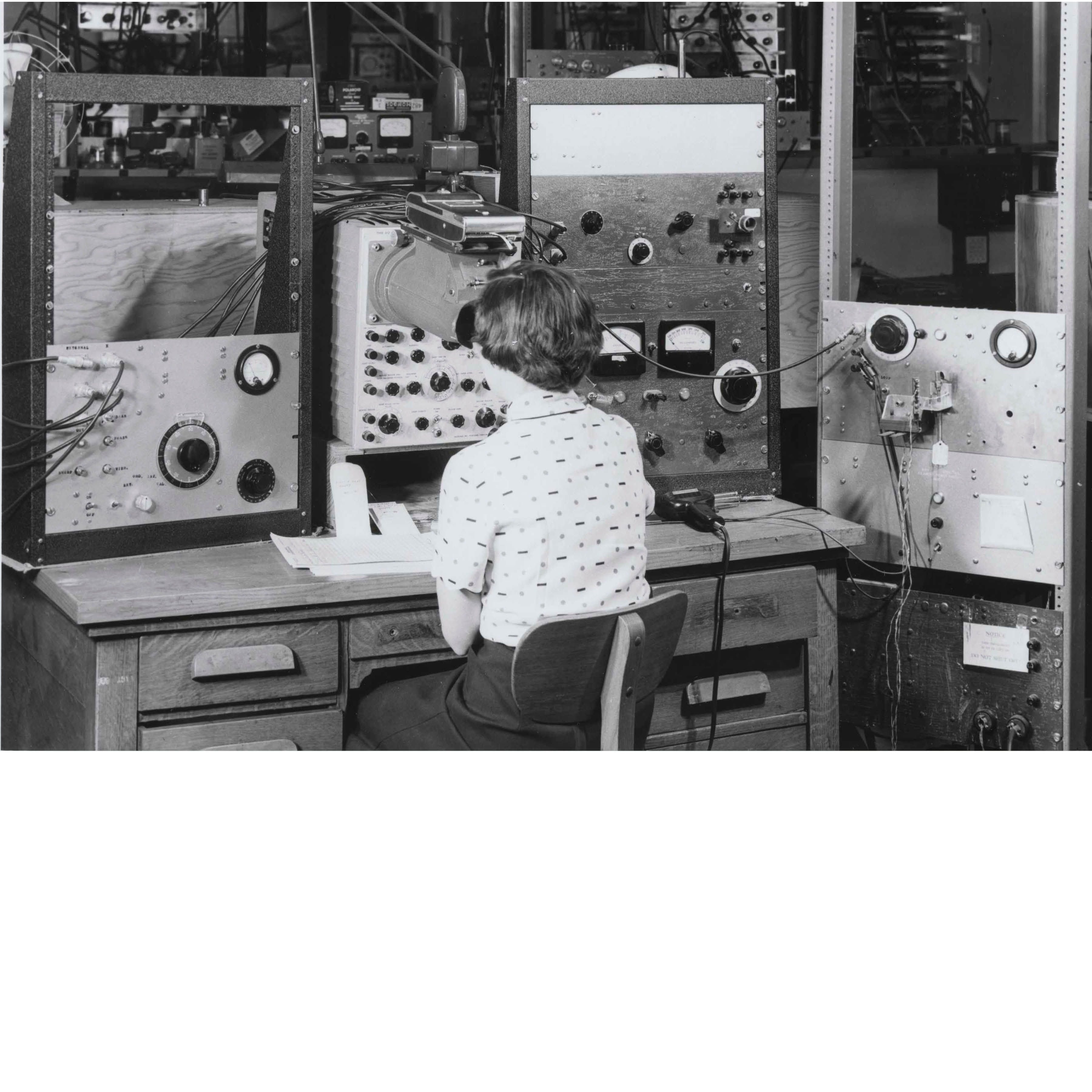

Opposite:

A (IM) - 2(24), 1954 - 1962, 45276

Woman with Magnetic Core Memory Plane Tester

Top:

A (IM) - 2(27), 1954 - 1962, 45276

Woman using Magnetic Hysterisis Loop Tester

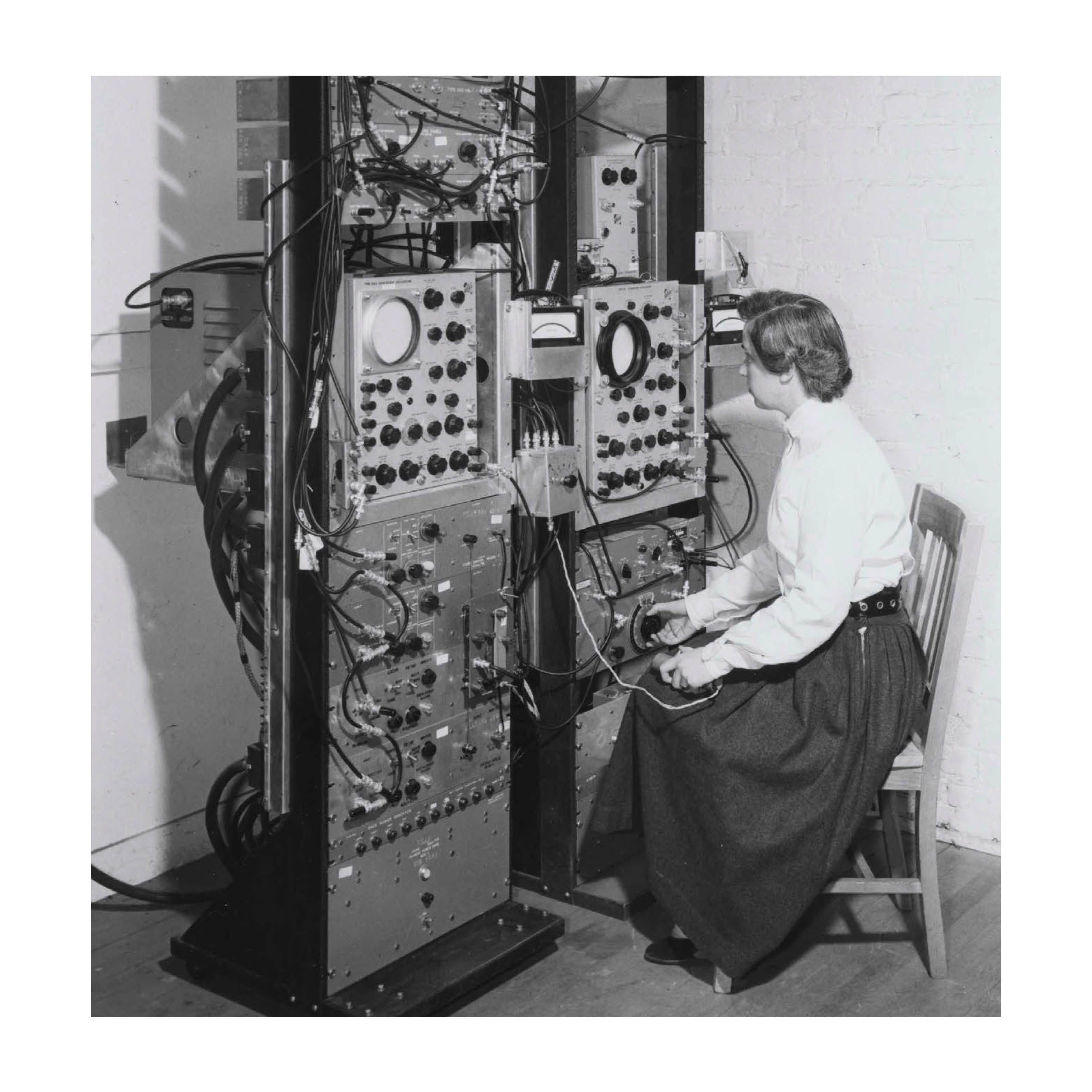

Opposite:

A (IM) - 2(24), 1954 - 1962, 45276

Woman with Magnetic Core Memory Plane Tester

Top:

A (IM) - 2(27), 1954 - 1962, 45276

Woman using Magnetic Hysterisis Loop Tester

Opposite:

A (IM) - 2(24), 1954 - 1962, 45276

Woman with Magnetic Core Memory Plane Tester

Top:

A (IM) - 2(27), 1954 - 1962, 45276

Woman using Magnetic Hysterisis Loop Tester

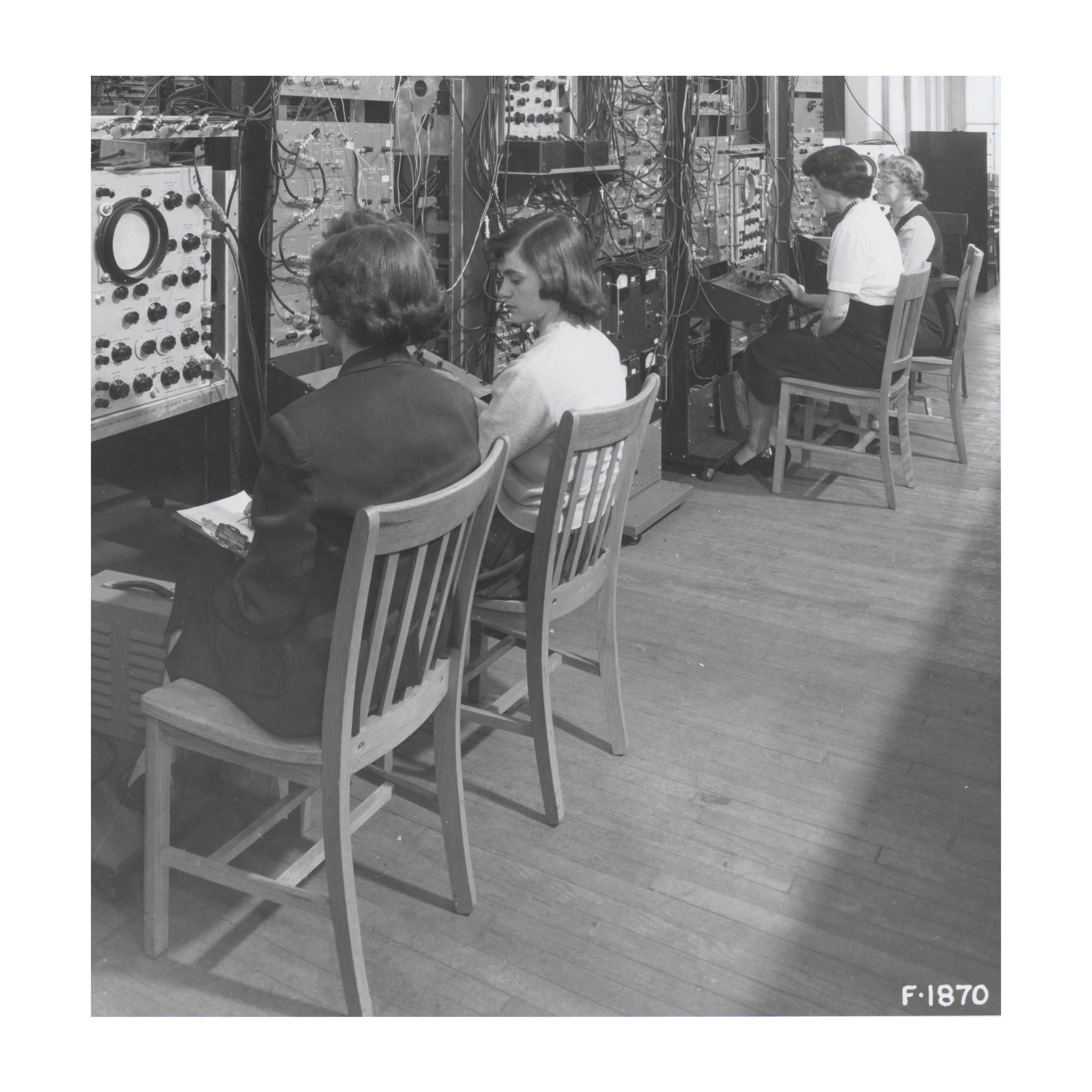

Opposite:

A (IM) - 2(29), 1954 - 1962, 45276

Women Testing Ferrite Cores

Girls, Weavers, Little Old Ladies, Space Age Workers

For a single component of the AGC, computer software was created from weaving half a mile of Nickel alloy wire through 512 magnetic cores, based on the punch cards derived from the sheets of code. This work required precision and accuracy that only few people could muster. As it happened, women from the textile and watchmaking factories local to Massachusetts, renowned for their sewing and fine-motor skills were employed to carry out this task of fabrication. They had the fine motor skills to weave the lengths of wire accurately.

”Every bit had to be sewn with a needle and a thread-like wire through these little magnetic cores,” said David Mindell, Author of Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Space Flight. “There were all these women sitting at these stations threading the needles, sewing the software bit, by bit, by bit, into the cores and they had to do it with 100% accuracy with thousands and thousands of different bits.”

“When the programmers finally figured out what they wanted to do for the mission, they would release a deck of (computer punch) cards that went to the machine in Waltham,” .The women “had to work very fast. They would have to get this thing built in time to get it shipped down to (Cape Canaveral) and installed, checked out and be ready for the launch. Every mission went through this same kind of a crisis to get these core ropes built in time.” Each memory module was tested extensively by Raytheon before being delivered to NASA. Mary Lou Rogers, of Waltham, worked on a different part of the Apollo production line, but in a recent BBC interview, she recalled the testing process.

Each piece “had to be looked at by three or four people before it was stamped off. We had a group of inspectors come in from the federal government to check out work all the time,” she said.

Occasionally an error would be found before it was “potted” in a heavy epoxy to avoid corrosion. “There was some very limited ability to go in and change a bit here and a bit there,” Mindell said. But, if an error was found after the potting, Poundstone said it was not generally worth trying to fix it. “They just threw the whole thing away.”

Excerpt from When Waltham went to the moon: Area companies helped Apollo 11 .

Opposite:

B(IM) - 1(5), 1960s, 2019

Female workers in Raytheon factory weaving Core Memory Planes

Left:

E(IM) - 17(1), 1969

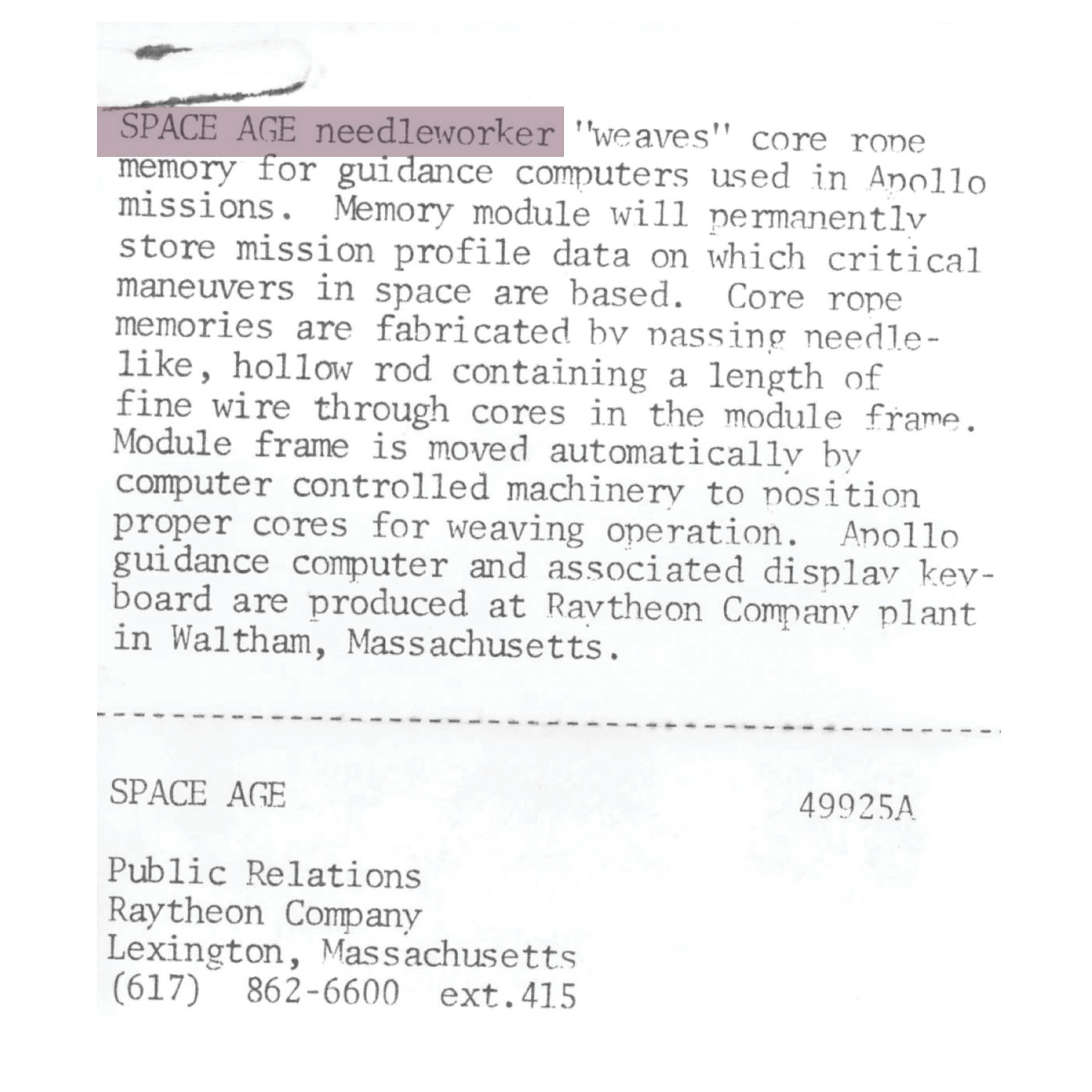

Scan of press release with caption describing woman in 17(1) as a “space age needleworker”

Labor

While compiling the archive, we came across a news article from Boston Globe about a strike that took place in 1966 at 12 of Raytheon’s plants in Massachusetts. The plant at Waltham where woven memory was manufactured is mentioned directly and although further investigation into the striking Union member rolls were unsuccessful, this article raised questions about the working conditions of the women who were involved in the project.

Opposite:

NC-1, 1966

10,000 strike at Raytheon, pg 1 Source: Boston Globe

Top:

NC-1, 1966

10,000 strike at Raytheon, Mediator hopes to reach both sides, pg 2

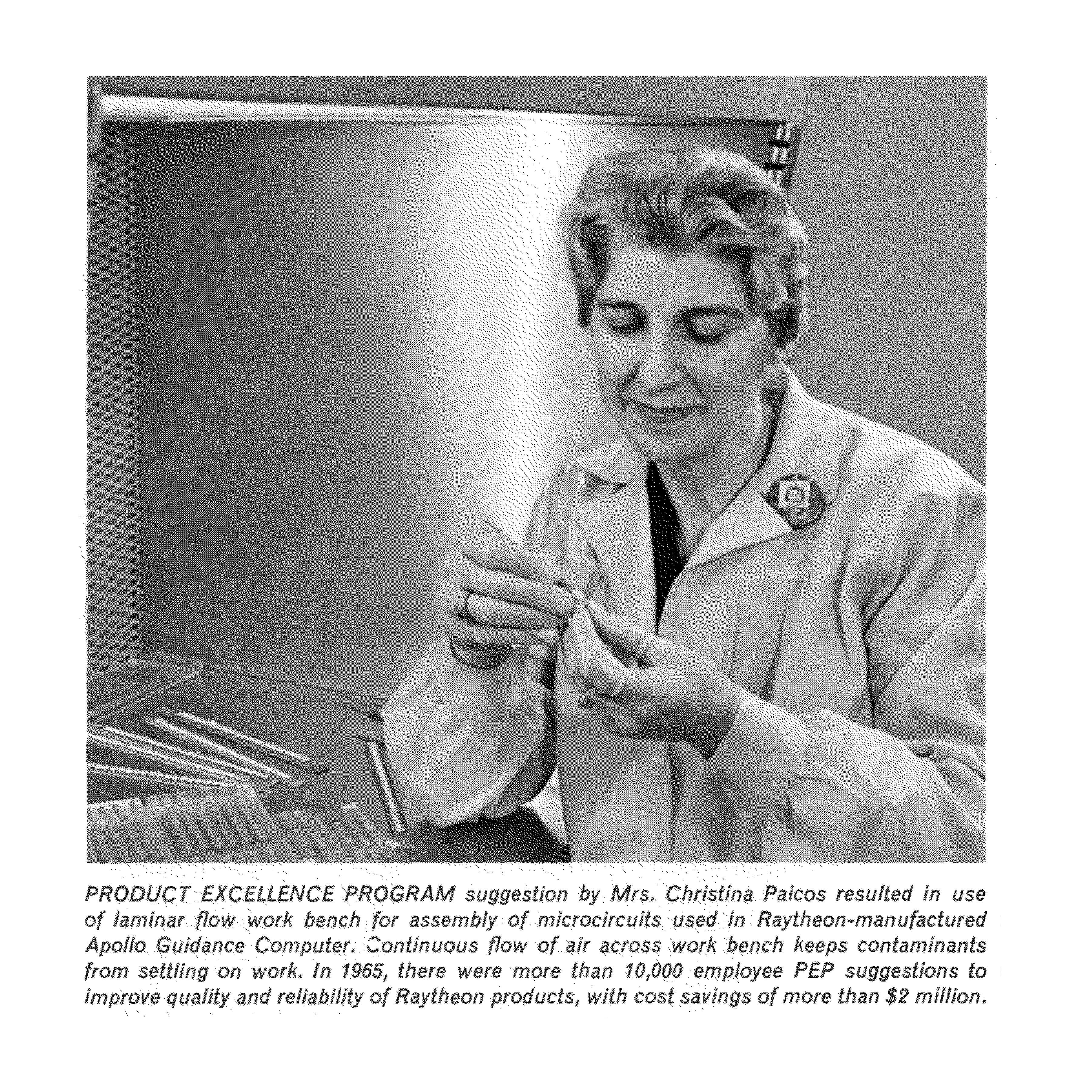

Although not much is written about thee working conditions of the ‘weavers’, In the above 1965 Raytheon article, a suggestion by Mrs. Christina Palcos is highlighted. According to article, her suggestions resulted in the use of laminar workflow benches for the assembly of microcircuits used in the AGC, the result being the prevention of contaminants from settling on the work.

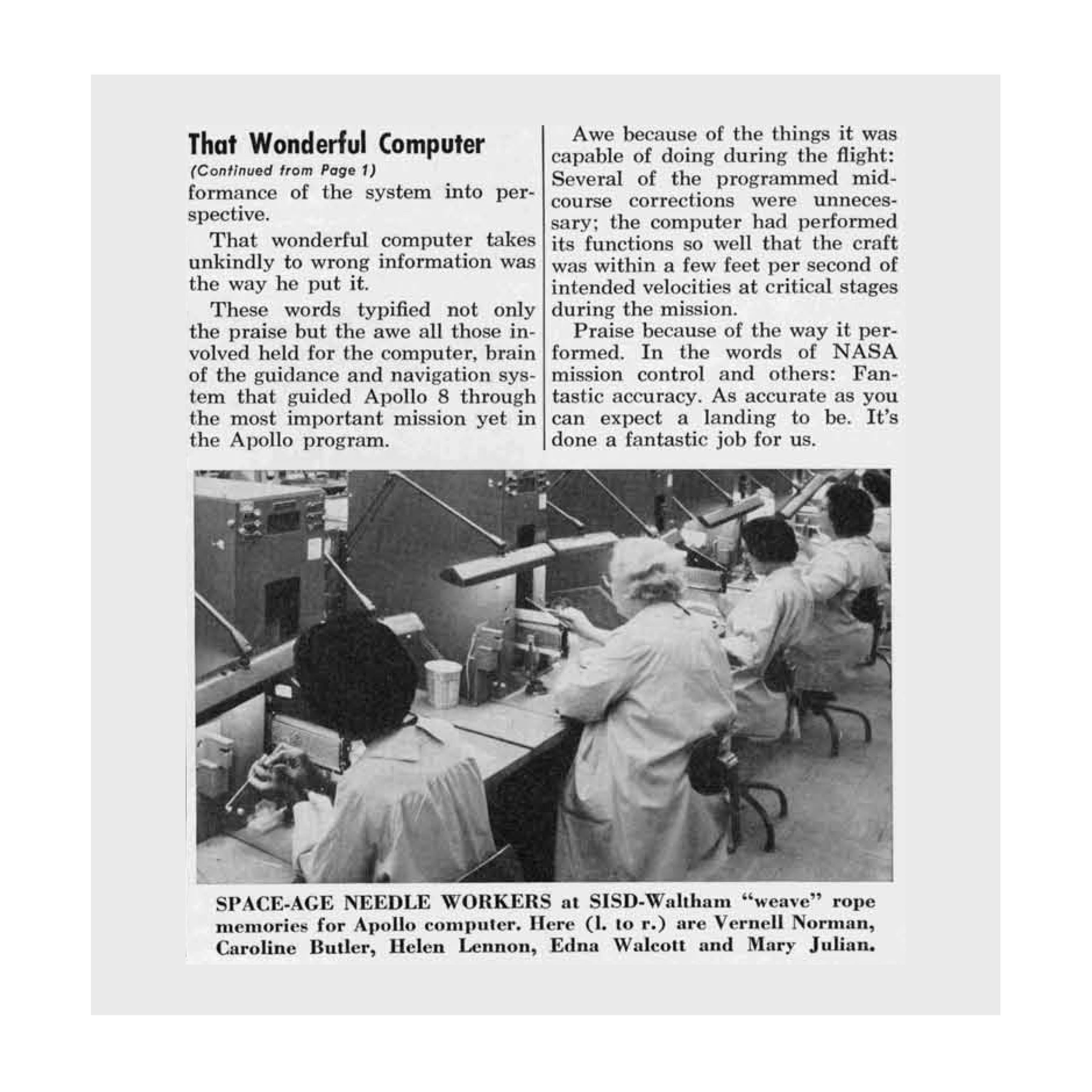

In this news Article released by Raytheon, ‘space-age needleworkers’ are again highlighted and in this instance, named directly. Vernell Norman, Caroline Butler, Helen Lennon, Edna Walcott, Mary Julian. From the image, it seems that the workflow bench suggested by Mrs. Christina Palcos was indeed adopted, when you compare with older images documenting the factories where woven memory was manufactured.

Opposite:

NC-2, 1969

Raytheon News February 1969 Volume 18, Number 2 - Page 3

Left:

R-5, 1965

Raytheon Company Annual Report 1965 - Page 15

Assembly

In ‘Eight Years to the Moon', Nancy Atkinson writes that the integrated circuit chips were welded into subassemblies for the Apollo Guidance Computer. In a conversation with Douglas St Clair, who worked in quality control at the Raytheon Facility in Waltham at the time, he recalled "The Integrated circuits were the shape of two graham crackers stacked on top of one another with ten flat leads - or wires - five on each side, coming out from between two crackers”. The integrated circuits were about 1/2 inch square. There were no solder joints in the computer and all connections were welded and gold plated, which provided a more secure connection.

Although the welding was done by hand, a special machine called an infrared pyrometer measured the flash of light from each weld to ensure the proper welding temperature. Each weld was made under a microscope and the operator carefully examined each bond after it was made.

This assembly stage of the integrated circuit chips is another in a long line of manually demanding tasks that according to documentation images such as the one to the right, was designated to the female workers.

Opposite:

B(IM) - 1(4), 1960s, 2019

A Raytheon employee working on the Apollo Guidance Computer micrologic subassembly.

Opposite:

E(IM) - 31(1), U

A Raytheon employee working on the Apollo Guidance Computer Micrologic Assembly